Specialty Coffee: International Booker Prize 2025

This was incredibly fun and I cannot wait to do it again next year.

For years now I had in mind to actually read the entire shortlist of numerous fiction awards, but this is the first time I actually planned ahead1. I think the International Booker Prize was the best choice, for me, personally — the books are incredibly diverse and were on the short side this year (I’m a bit sad Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu did not make it, but, hey, we wouldn’t be here if it did because that book is massive).

Reading all the books and knowing the judges had to read the longlist and then reread the shortlist a bunch of times, all I can say is chapeau bas. Reading is so absurdly subjective to me that I’m not sure how these people will decide the winner (hopefully they will choose one of my favourites).

Without further ado, let’s discuss them (in the order I read them in).

On the Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara J. Haveland

“That is how the days began: with an undefined morning. There is the grey light from the window. There is the birdsong, the sound of rain. There is the feel of the bed linen against my skin, the faint sound of the wind in the trees, a soft sighing in the morning air.”

Tara wakes on 18th November day after day, again and again. She is the only one who remembers that yesterday was also 18th November and the only one who knows that tomorrow will be 18th November. For everyone else, time resets. They experience the day as if for the first time.

How many times can you repeat the same day over and over? How do your relationships change when you are the only one for who time moves forward?

I bloody loved it.

On the Calculation of Volume I is a quiet meditation on love and human existence. It shows that the mundane, even though repetitive, can still hold deeper meaning. At the same time it’s an exploration of loneliness.

Balle’s craft made this book so hard to put down, yet I wanted it to last forever. You really need to master the way you tell a story if you are writing a time-loop. It’s repetitive without boring the reader as it’s in this repetitiveness that we find hidden meanings. Tara keeps waking up on the same morning, yet she is not the same as she were last time she experienced the same 18th November.

“The fog had lifted. Those strange days were past. I knew I couldn’t hold onto the morning’s hazy gray light for long, I knew that I had been keeping the past and the present out, that I had been like a human pilot light. Gone were the featureless mornings. Gone, my time at the bottom of the sea, gone and irretrievable. Gone, the fog which had been the greatest bliss but which — it seems to me now — requires one to be in a state of the utmost naivety, to dwell in the halls of folly, to surrender to the gentle grip of apathy.”

What vibed with me:

There’s a palpable stillness in the air, yet there are subtle changes. Noticing things, paying attention becomes imperative. It’s an equation — and there’s a lot of metaphorical (and literal) math present in this book. It made me question a lot of things about life and about myself.

Most importantly though, I found myself in this book as I never did in any other book. It made me reflect constantly.

Oh, and it’s the first book in a series of seven. At this moment I cannot imagine what Balle can do more to this story, yet I am excited. I’m someone who doesn’t usually go for series, but On the Calculation of Volume I feels complete in its incompleteness.

What didn’t:

No notes.

A Leopard-Skin Hat by Anne Serre, translated by Mark Hutchinson

“Her life even seemed to come together, her emotions to fall back into place. As if doing a little harm could do you a little good, not because it gave you some unspeakable thrill (certainly not) but because it instilled a certain gravity in you, whereby you began to resemble the rest of the world, the ones who live, who somehow manage to live.”

The Narrator reminisces his relationship with his childhood friend, Fanny, in the aftermath of her passing. It explores the ups and downs that are natural for a friendship but also plays with the images we build in our heads about others. It’s a story of grief and memory. And it’s very French.

Unfortunately I felt like I couldn’t get a sense of the Narrator or Fanny, which we only see through his eyes anyway — and btw, the story is told in third person. While we learn Fanny’s story through various episodes from the Narrator’s memories, how reliable are his memories? Who is the real Fanny and how different is she from his perceived image of her?

This novel is quite experimental — short episodic chapters revealing memories not necessarily in a chronological order, an omniscient narrator (not to be confused with our Narrator) who enjoys breaking the fourth wall, and a beautiful delicate prose.

“Basically, the Narrator said to himself, the idea we form of others comes solely from their relationship with ourselves. Seen through their relationship with someone else, they are necessarily slightly different. And should we catch a glimpse of them in the privacy of their own self (which is impossible without spying on them or rummaging through their papers) they are someone of whom we know strictly nothing.”

What vibed with me:

The little tidbits of introspection I found myself in (can you tell I have a type?) — for instance when the Narrator has a hard time seeing the other humans as more than episodic characters in his life, as fully-fledged humans capable of an entire part of life he is not privy to. The novel touches a lot on our perception of others.

And, of course, the writing. I found the prose exceptionally beautiful.

What didn’t:

I couldn’t connect with the story itself or its characters — albeit it’s not easy to connect with them as we only see Fanny through the Narrator’s memories and we need to read between the lines to find out a bit more about the Narrator. There is a point in the story when he opens up and reveals some information but no more is said, which was rather strange.

While I liked the prose, I admit the structure of this novel was not as easy to follow. Granted, I was on a family vacation and probably not in the mood for an experimental story on grief. I was rather bored while reading it, yet upon finishing it I kept thinking about it for weeks.

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated by Sophie Hughes

“From the outside, it was easy enough to identify the cause of their alienation, but to them, paradoxically, no explanation revealed itself. Anna and Tom lived in a bubble, one even more insular and limited than those just starting to appear on social media. In a way, they had become radicalized. They spoke stumbling English with other non-native English speakers. They inhabited a world where everyone accepted a line of coke, where no one was a doctor or a baker or a taxi driver or a middle school teacher. They spent all their time in plant-filled apartments and cafés with excellent Wi-Fi. In the long run it was inevitable they would convince themselves that nothing else existed.”

Millennial expat couple Anna and Tom are living in a grand aesthetically pleasing apartment in Berlin. Their life on social media seems perfect, but there’s something missing, a hole they don’t quite know how to fill, and galleries, Scandi furniture and sexual experimentation don’t do the trick. Are they just looking for a place that maybe feels like home?

Welcome to the novel that might be just like a mirror, ready to make you question your entire life. Millennial-core, globalization, capitalism, alienation. You name it, this novel has it.

Anna and Tom are not characters, they represent an entire generation. We are not supposed to actually know them or get close to them. The novel is satire. Anna and Tom are just prototypes — they are the millennial couple, with the indoor plant-jungle and their minimalist apartment, but also an unbearable feeling of dislocation. They are supposed to be everyone and no one at the same time.

The idea is quite clear but the execution felt rather shallow. I’m not saying I wanted to care necessarily for Anna and Tom, but I’m sure the point wasn’t to dislike them either.

Surprisingly there is no dialogue and even though it’s full of very detailed and descriptive prose, it doesn’t feel heavy or flowery. In spite of that, this book flows! It’s quite minimalist in its maximalism. Realism at its finest.

“These new emotions weren’t all negative. What was that rush they would get after a particularly popular post? And the itch that made them look up from their work every twenty seconds, every minute, to refresh the page and watch the number of likes clock up, as if it were a stock ticker or a scoreboard? They felt it every day, and yet that feeling had no name. It wasn’t a scoreboard – there was no prize at the end. Financially speaking, it had very little impact, if any. Fifty-year-old sociologists would talk about narcissism, but they were only talking about themselves. Pop-neuroscience journalists would write about it in terms of drug and sugar addiction and depression.”

What vibed with me:

I complained about it, but paradoxically I also enjoyed that we are not allowed to get too close to Anna and Tom. I liked that the novel deliberately forces me to do something I don’t like to do: to be detached.

It made me question my own relation with social media and this weird need to share an instastory or a tweet. Why? I’m still contemplating it.

What didn’t:

Look, I probably would've been mad about this book if it weren't written by a millennial, but alas, Latronico is just presenting a critique of its own generation. That being said, it left me wanting something more.

Under the Eye of the Big Bird by Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Asa Yoneda

“You have the ability to feel satisfied simply by exercising your ability to choose- even when the choice itself has only the barest chance or succeeding.”

Welcome to the peculiar speculative novel presenting a future in which humans are almost extinct, thus we are left wondering what would happen to humanity. A question to which Hiromi Kawakami gives us plenty of answers.

For the full effect of it, go in as blindly as possible — I will keep my review of it brief and evasive. Being confused for more than half of the book is part of the ride.

The story is told through interconnected stories where different characters pop in and out, with some categories of characters more present than others and you will continuously wonder about them — who are they? what’s their mission? are they even human?

The writing is detached and cold, almost clinical at times, which adds to the weirdness of it all. The timeline is fragmented and the short stories are not presented in a linear order. The novel builds itself as a puzzle that the reader must put together.

“You’re a little inquisitive. That’s fine, of course. People ought to have a thirst for knowledge. Life is short, after all.”

What vibed with me:

I usually prefer to know as little as possible about the books I read (don’t ask me how I decide which books to buy, you will not like my answer) and I felt this way about every short story in this book. It was confusing as hell — read that as tons of fun. I like puzzles, especially in book form.

Even though the writing is cold, at its core this book is about our humanity and that contrast was very beautiful. Plus I really enjoyed how the author plays with our sense of time and different narrative perspectives.

What didn’t:

There is a chapter that ties in all the loose ends and explains the entire book. I’m never a fan of that in books (or films or anything). It feels like the author didn’t trust me enough to put the book together and come to my own conclusion.

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi

“Material things had become priceless and human beings worthless. Behind those material possessions, people’s feelings were on sale.”

This is the only volume of short stories on the shortlist — short stories written between 1990 and 2023, that capture the daily lives of women and girls in Muslim communities in southern India, offering a female perspective on family dynamics.

The author is also a lawyer and an activist, critical of the caste and class system.

Even though the stories were written in the past 30 years, you don’t feel any discrepancies in the writing style — I’m not sure if this is due to the translation (this is Banu Mushtaq first work translated in English). And while we are on the translation, some choices were made to not use italics or footnotes for the words that remained in their original language. A lot of reviewers I follow found that challenging, but personally I loved it because it allowed me to immerse myself even more in the world and culture presented here. It also prompts you to research yourself, but the context is enough — maybe the first stories will be harder to follow.

The book is very important in showcasing the subjugation of Muslim women and this is not just about religion (women are treated as second class humans in most religions). The stories are full of tension, but also dry humour.

“You gave me the strength to bear a lot of pain. But you should not have given him the cruelty to cause so much of it.”

What vibed with me:

To my shame, this is probably one of the first books I read from India and even more so about Islam (I also read some books by Khaled Hosseini but I’m not on good terms with his writing). I liked learning about the culture — at times it broke me and it made me grateful for the part of world I was born into.

The religion is present in the book, but it’s not the subject of it nor is it highlighted or judged — it’s simply woven into the stories, always present.

What didn’t:

The stories are quite repetitive and hard to follow because of the large cast and the rushed action.

It might just be me, but other than the subject of the stories and the translation choices, I did not really see why the book made the shortlist. Reading is very subjective, of course.

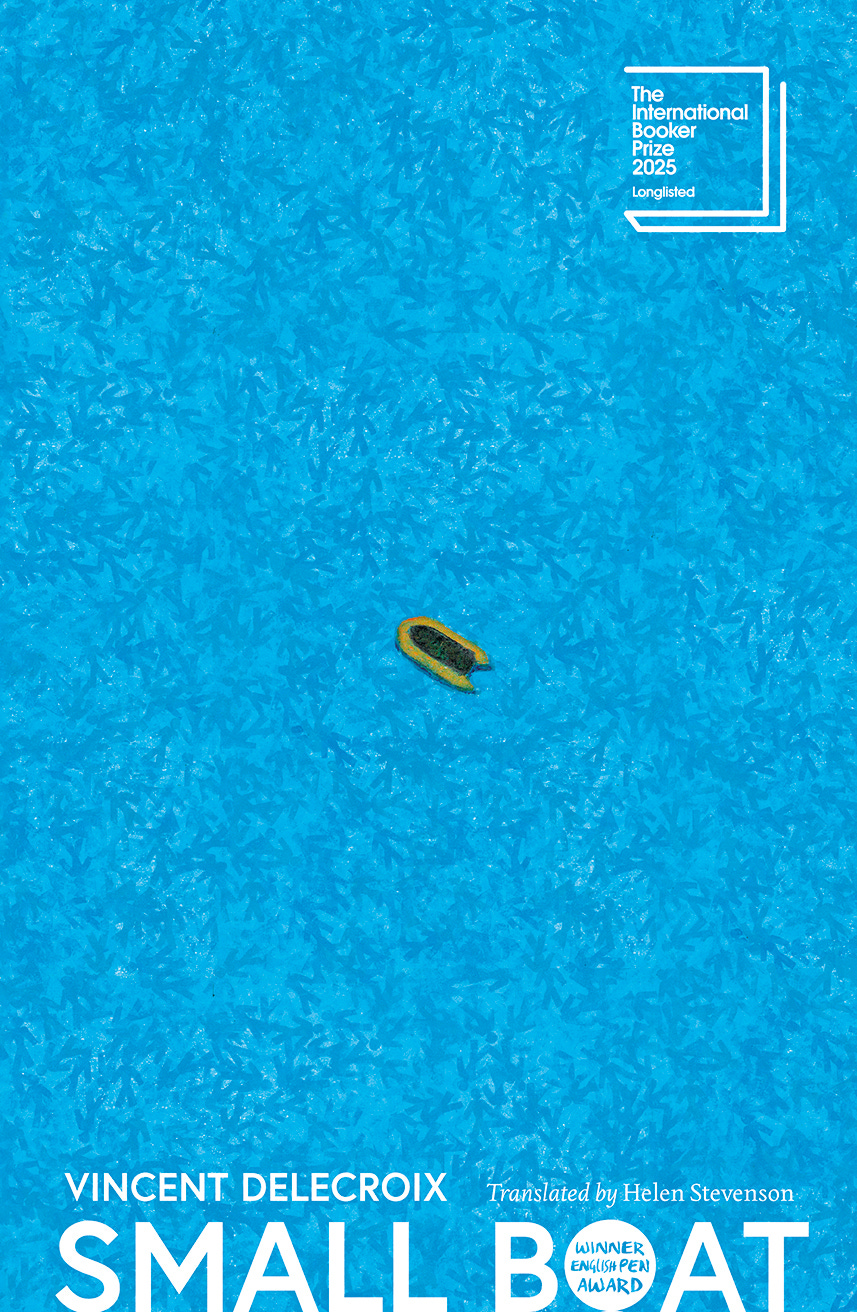

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix, translated by Helen Stevenson

“It was your idea, and if you didn’t want to get your feet wet, love, you shouldn’t have embarked. I didn’t push you into the water, I didn’t fetch you from your village or field or ruin of a suburb and put you in your wretched leaky boat, and now the water’s up to your ankles, I get it that you’re frightened, and you want me to save you and you’re impatient. You’re counting on me. But I didn’t ask you for any of that. So you’ll just have to grin and bear it and let me get on with my job.”

Based on a real-life tragic event — 27 migrants died trying to cross the Channel from France to the UK, Small Boat is told from the POV of the operator from CROSS who took their distressed calls.

Small Boat forces us to confront the harsh realities of the migrant crisis and it challenges us to consider our own role in it. And it does all this by placing us in the mind of the most unlikeable character ever! Brilliant!

This novel offers the most detached piece of introspection that I’ve ever read. It’s structured in three parts, two from the POV of the operator and the middle being a short glimpse at the migrants on the boat. I think this showcases Delecroix ability to write both a somewhat uncaring or rather stunted character, but also very tense emotional moments on the migrant boat.

Up until this point my choice for the winner was locked in. Now I am not so sure.

“I know people would have liked me to say: You’re not going to die, I’ll save you. And not because I would have actually saved them, done my job, done the necessary, sent rescue. Not because I’d done what you’re meant to do. They wanted me to have said it, at least to have said it, just to have said the words.”

What vibed with me:

By far the writing and how the book asks so many questions yet it never gives the reader any answers. It lets you challenge your own ideas on morality and it makes you uncomfortable. Are we all complicit? What’s our collective responsibility? Are we really that desensitized?

What didn’t:

No notes.

My Prediction: If it wasn’t obvious by now, my top favourites are On the Calculation of Volume I and Small Boat. Such different books. While I have a more personal attachment to On the Calculation of Volume I, I think Small Boat should win (and I hope it will).

The winner will be announced tonight!

Thank you for reading!

This is a lie — the idea came one night while discussing with a friend. The timeline just fit so we were able to actually put the plan in motion.